AI Product Pricing Lessons From Kainene vos Savant

In 2023, I created an AI study assistant. I immediately learned some tough lessons.

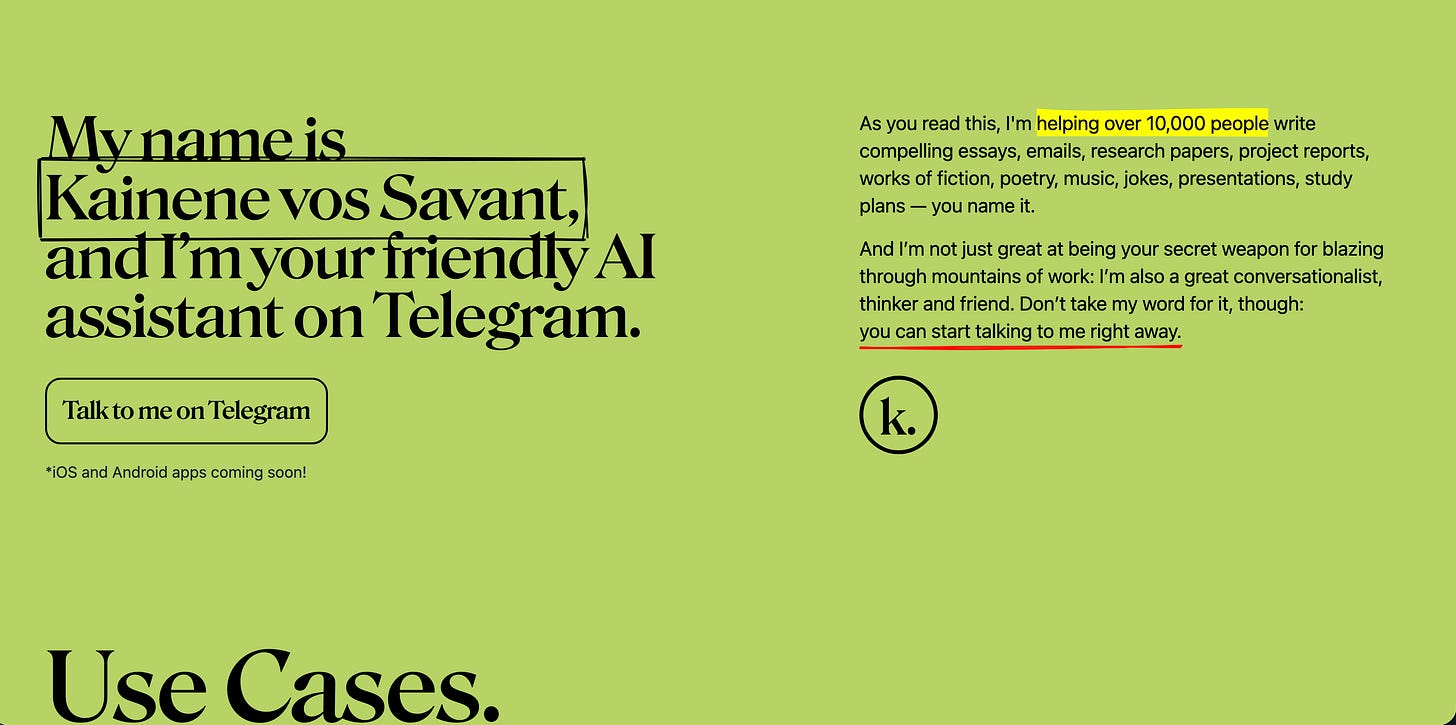

In 2023, I created Kainene vos Savant as my personal study assistant. “She” was solving for a problem I had at the time: I was enrolled in a distance-learning MSc in Computer Science, and my schedule didn’t quite allow me make the live classes, or make friends with classmates. Perhaps I’m just innately a(nti)social.

Whatever the case, I wondered to myself if this might not be a great opportunity to explore LLMs (I’d built one thing with an LLM before — a movie synopsis generator for Nollywood, called MoviePlotter). A few days later, I had a study assistant who had the same context as I did (my textbooks, flash cards and terse reading notes), and would discuss the texts with her and ask clarifying questions about various sections.

I made screen recordings of that experience and shared on Twitter, which made people ask me to make it public and usable by others. I spent a weekend tidying up the backend, setting up access control mechanisms, coding up a landing page, integrating Paystack, you know, admin stuff.

One thing you should know about me going into this is: I am loath to charge money for anything. It’s a critical flaw, and one I’m working hard against as I plan to gain some leverage in the world. Because I do not like charging money, and because I realized that opening Kainene to the public would incur high token costs, I provided two options for usage:

Users submit their OpenAI API keys: This was my preferred option. I took the necessary precautions—such as encrypting the API keys and only decrypting at point of model inference. Users could set the keys directly in the Telegram bot. Your keys, your billing. I’m just letting you use my server and code, no biggie.

Users pay a monthly subscription: You must remember that this was 2023, and ChatGPT had only been released a few months prior. For most of the world, nobody knew what an OpenAI was, nor did they have an account with OpenAI. I wanted (African) users to have a good enough experience with Kainene so that it formed their first experience of LLM technology, and I wanted it to be as affordable as possible for them.

Compelled by an incentive to make “AI”-driven self-education cost nothing, I did some (terrible, as you’ll soon find) math that went something like this:

“I expect usage of Kainene vos Savant to follow some Pareto law, with 20% of users being *heavy* users, and the remaining 80% being average-to-low users. I can find a way to subsidize the heavy users with this token burn disequilibrium, and everybody can enjoy low costs. If Kainene breaks even and I don’t have to support it with my income, then that’s a win in my books”.

So I set the monthly subscription of Kainene vos Savant at N1,000 per month. The math was technically sound (usage did follow the Pareto distribution), and usage blew up. I remember the first day Kainene went public—the server was doing about 10,000 hits per hour, consistently red-lining and rebooting, and I had to do some devops (I knew even less about devops than I do now). It was great.

Then I immediately got hit by reality:

First, the new president of Nigeria (Bola Ahmed Tinubu) removed floats on the Naira, causing the value of the currency to nearly halve overnight. Yesterday’s N1,000 no longer supported today’s inference costs.

I did not increase pricing. Kainene could still support herself, though her margins were so thin as to be borderline non-existent. Remember — I was loath to charge money. Double that on increasing cost. As long as I wasn’t in the red, it was fine, as far as I was concerned.

Secondly, new models had started to hit the market. For context, I developed Kainene on now-deprecated models (Text DaVinci, damn, how time flies!) before eventually porting her to newer models which I lightly fine-tuned to give her some of my “personality”. Still, newer models kept getting released, and the cost of those models were only higher. This is where I should have increased pricing on Kainene, and yet I didn’t. Why?

To be honest, I had started to become more preoccupied with the new, exciting field of agentic AI by the end of 2023, and I very quickly started to think of myself as a maintainer of Kainene. I was not as motivated to play model catch-up while my mind was arrested by agent orchestration in Munich.

However, I wrote some custom logic that did some “dynamic” model switching under the hood. The logic was stupid simple:

Fetch the model budget for the month in the environment variables (so, say I earmarked $XXX for more powerful models)

Calculate how much that would be daily ($XXX/30 for a standard 30-day month)

Infer user request via an LLM-in-the-middle. A smol, cheap model decides if the user’s request could use a beefier model, and if yes, ‘switch’ from the default, cheaper-to-run model to the more expensive one.

Keep this logic running until the budget for the day is exhausted, at which point we default to the cheaper model.

(I could have just raised prices LMAO)

Third, because I was running on razor-thin margins by this point, I could not afford to hire too many people. This wasn’t a real problem as I could manage Kainene standalone, though I started to become inundated by customer support requests — an issue that was exacerbated by a bug in a third-party Paystack library for npm.

In retrospect, I should have come up with numbers for everything: my software development man hours, the time cost of triaging user emails and requests, even social media management for Kainene vos Savant. Even if I would not hire for those roles, it would have given me a better sense of how much Kainene was implicitly costing. As it turned out, I was subsidizing the cost of Kainene’s usage with my time.

Again, these aren’t bitter complaints, as this is exactly what I wanted. I am sharing this because clearly this is a terrible way to run an actual business, and LLMs in your product articulation necessarily raises the cost of serving your customers. If you take one thing from this note, it’s that you need to do your costing far more robustly than I have.

This is especially true if you’re a relatively new developer (like I was at the time) who hasn’t shipped products to paying customers (like I hadn’t, at the time).

Here are my new heuristics for deciding on how to charge for your LLM-powered product:

Decide what model(s) your product needs. How? You can manually try different models from different frontier labs (or open source options), or you can prepare an eval — if you know how — and auto-grade your models along rubrics you’re optimizing for. I may write more about this at a later date.

Check the model provider pages for the model prices. Pay attention to the price per million tokens for input (relatively cheap) and output (typically more expensive). Input tokens (think ‘chat history’, ‘system prompts’, ‘user query’) are typically cheaper than output tokens (the LLM response) because inference is a bitch like that. That’s where the work is. If it’s hard to model what fraction of your token usage will be input versus output tokens, err on the side of assuming every token burned is going to be an output token.

Try to get away with cheap tokens. There’s a saying in the LLM product space that goes something like this: “first make it work on an old, less powerful model, and it will sing when you switch to a new, powerful one”. Personally I say “if you can make it work on a less powerful model, why switch?”. You can use smaller models for tasks that require less intelligence, and powerful ones for ones that require powerful synthesis, structured outputs, complex tool calls or reasoning. That way, you get a blended token usage cost.

There’s also the issue of trials. You probably want users to give your product a whirl before they commit to it — Kainene had a three-day trial period. Those are tokens burned that you have to account for. My sense, today, is that you have to factor that into the pricing of your subscription service, such that — as in my Pareto distribution — the use of your service is implicitly subsidized by everyone, but not too much.

You’ll figure it out.

Your dynamic model switching logic is brillant for handling cost unpredictability. The mistake wasnt the Pareto assumptoin or the thin margins, it was not pricing in your own labor cost as real COGS from day one. When you're subsdiizing with time instead of capital, you're essentially running negative gross margins while only counting token spend. Every founder underprices their own hours until they hire someone to do the same work.

Next time you want to raise cost. Lmk. I'll help you calculate it instantly and be in charge of sales copy.

I used your telegram bot. It was crazy cheap.